The Enchanted Laboratory show

One of the most creative regional park shows I’ve seen was at Busch Gardens Williamsburg. It ran from 1986 to 2000 and was the work of several amazing designers, some of whom were connected to Disney in some way and went on to make a big dent in the park entertainment universe. The best source for information on the show is by Peter Wood, a superfan who’s built the ultimate tribute site, enchantedlaboratory.com. He’s the author of the following article on the show and has graciously offered to share it with us. So, read the amazing story and go check out his site. These are the kinds of treasures we want to hold on to. And now over to you, Peter…

History of Enchanted Laboratory

Busch Gardens, The Old Country opened in Williamsburg, Virginia in 1975. Among its opening day attractions was The Catapult, “a breath-taking scrambler ride with unexpected confrontations with knights of old” according to the park map. Themed after the 1066 Battle of Hastings, Busch Gardens had assembled this classic flat ride inside a building, complete with scenery and props, special lighting, sound effects, and a Scottish castle façade built by Snow, Jr. & King.

“The Catapult was a fun ride,” explains Joe Peczi, former Corporate Director of Entertainment for Busch Entertainment Corporation, “but being indoors and out of sight meant that not many guests knew what the Catapult ride was since they couldn’t see it. The appeal for such a ride is largely due to seeing it in operation to spur ridership.”

In the early 1980’s, Busch management decided to move The Catapult to an outdoor location elsewhere in the park, which left an empty building in Hastings.

“I put my hat in the ring for a possible show concept to fill the space being vacated,” Peczi says. “I wrote up a rough story concept, along with justification for why I thought the show concept would be a far better use of the existing building. While rides are popular with kids and a certain demographic of park guests, there are some people who won’t ride any rides regardless of how tame they may be. A well executed show, however, has a broader age appeal. Disney was already adept at presenting engaging animatronic shows such as The Enchanted Tiki Room, The Country Bear Jamboree, Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln, The Carousel of Progress, and others. Each of these shows could be presented constantly on a daily basis without high operating costs.”

As appealing as an animatronic show was from an operations perspective, Joe felt there was something missing. “Even Disney’s beautifully designed and constructed animatronic shows, while very entertaining, were not able to provide audience interaction or a response by pre-programmed mechanical figures alone,” he explains.

Peczi came up with the idea of a hybrid show and pitched his idea to senior management at their annual marketing meeting. The show would star an unseen sorcerer named Nostramos, an animatronic dragon and raven (an owl would later be added), and a live actor portraying an enthusiastic apprentice named Northrup. “Emphasis was placed in my presentation upon the proposed live interaction Northrup would have with the audience,” Joe recalls, “which would include magic and illusions, audience participation, and a one-on-one relationship with the animatronic animal characters that would make their interaction with Northrup more believable. While show concept and budget numbers were the primary content of the proposal presentation, I knew that some visual representation of the story concept would likely enhance the overall presentation.” Joe created two renderings, drawing inspiration from his visits to European castles, as well as a lifelong interest in magic and illusion.

“I left the meeting with a very favorable response to the show concept,” Peczi recalls, “and was given the ‘green light’ to pursue the concept further. The lengthy, and very technically intricate process that followed resulted in the project that became The Enchanted Laboratory of Nostramos the Magnificent.”

To develop the show, Peczi reached out to two creative gentlemen: Mark Wilson and Gary Goddard.

“Now neither Mark or [I] knew it was a competition at the time,” Goddard remembers. “We each thought we were the only one.”

Wilson was Busch’s resident magician, having produced magic shows in the park’s Globe Theatre for several years. Goddard had recently left Walt Disney Imagineering to form his own company, Gary Goddard Productions (which became Landmark Entertainment Group shortly before Laboratory opened).

“By the time Joe [Peczi] got in touch with us,” Goddard explains, “Gary Goddard Productions had already done The Monster Plantation for Six Flags Over Georgia, The Great Texas Longhorn Revue for Six Flags AstroWorld, and probably most importantly The Adventures of Conan: A Sword & Sorcery Spectacular for Universal Studios Hollywood. I think Joe had seen the Conan show and was impressed. So he got in touch with us and explained what he was looking for.”

Ultimately, Goddard’s show concept was chosen over Mark Wilson’s, and the creative team began their work. Peczi “liked this kind of medieval setting,” writer and director Rich Hoag remembers, “that featured a cocky young apprentice who thinks he can perform the show when the wizard doesn’t show up. Unfortunately, his magic doesn’t hold a candle to that of the wizard, and he bungles most of the tricks.”

“Busch Gardens wanted a show with live performers to offset the rides,” associate producer Ted King recalls, “We wanted to create a family show full of music, fantasy and magic, and it just worked.”

“To make things really difficult,” Gary Goddard explains, Busch Gardens “said we could only have one cast member, and one tech. So that meant the show really had to work on its own. Coming from Disney, we immediately thought we could add some animatronic characters that our live host could interact with. We took the idea and blew it out to a much larger show concept.”

But the price tag—$1.6 million—was a gamble for Busch Gardens.

“I will say, though, that The Enchanted Lab was a huge risk for [Joe Peczi] and the company,” Rich Hoag acknowledges. “The corporate offices weren’t too sure if the show was a good investment. It was going to cost a lot of money at the time … To his credit, it was very successful.”

Designs for the show began in 1985, and took 8 months to complete. Scripts were written and revised, concept art was drawn, and eventually an elaborate model was built by Bob Baranick and Terri Cardinali to show how everything would fit together. Sixteen show elements (including the three animatronic animal characters) were built by AVG, and Technifex created several other effects, including the flying rig. Lexington Scenery, now Nassal ACM, “was new to the location-based entertainment business,” project manager George Wade explains. “So they were very aggressive in their pricing because they saw this as a growth category for them. Sure enough, they had a long, long run as one of the premier set producers for companies like Universal.”

“For the most part we got a version of everything we wanted in the show,” Goddard says, “including the gargoyles that come to life around the theater, and even the ‘imprisoned beast’ below, with the ability for our star to leap onto it as he tried to keep it from escaping.”

“It was a very tight budget,” remembers George Wade, “and it required a lot of cleverness on the part of the design and production team to be able to design all the elements, and then additional cleverness on how we went out and bought them. In some cases we had to sit down with vendors and say ‘Look, this is what we can afford. How do we get there?’ We were fortunate to have a team of vendors who saw the vision and really wanted to do the project, so that played to our benefit.”

In early 1986, The Catapult was dismantled, and moved to the Festa Italia area of the park. It is currently in the New France section, now renamed Le Catapult. Now free of ride equipment, a basement was dug under the building, to house the computer and special effect systems, as well as the space for it to emerge from.

“PGAV, the architects for Busch Gardens, were excellent design collaborators,” recalls Wade. “How do you take a building that was an indoor ride and convert it into a theater, with all the proper queueing and the required preshow area?”

One nod to the former attraction was in the preshow area, where a large mural depicting the Battle of Hastings wrapped around the perimeter.

“When we started rehearsals, the interior of the lab was just an empty building, still under re-construction from the days when there was a scrambler ride in the building,” remembers David Cole Snook. “The back of the building was expanded, and a basement was added to provide room for the huge smoke machine for all the fog effects in the show. We rehearsed in any blank space we could find until the main stage and set were installed.”

Once on site, the team from Landmark had to program the show, which was a painstaking process. David Thornton, who served as Laboratory‘s technical director and project manager during installation, was responsible for much of this work. “It was so hot in the basement with all the computers,” Rich Hoag notes, “and Dave would come up from the bowels of the basement dripping with sweat. Landmark made him a VP shortly after that.”

The animation of the characters fell to associate producer Ted King. “One of my mentors was the Disney Legend Bill Justice,” King explains “who programmed the animatronic characters on iconic Disney attractions such as Pirates of the Caribbean, The Haunted Mansion and Great Moments with Mr. Lincoln. He would have been proud to see me, some 20 years later, sitting in Williamsburg, programming Pellinore and Elixir. It was an amazing experience.”

As the show’s director, Rich Hoag was on site for about a month prior to opening, rehearsing with the first Northrups. Four actors were originally cast by Busch Gardens Entertainment, and they remained for the entire opening season.

“The animators set up a massive control desk in the audience of the lab,” explains David Cole Snook, one of the original Northrups. “All four of us were brought in and worked with them on/off through this process so the animators could focus Pellinore and Elixir’s movements. We had to do this over and over again so that the animators had the right angle with the birds and Northrup, based on the original blocking, so that the birds’ heads and up/down focus was correct. The overall rehearsal period for us originals was a multiple month experience.”

“I was there for the final week or programming and rehearsals, and of course, had been out earlier several times to check the progress,” explains Gary Goddard. “My memory is that things went about as well as they could.”

George Wade agrees. “Quite honestly, we were fortunate that everything worked the way it was supposed to. It was a magical project on a number of levels, and one of those areas was that things fell into place; we didn’t run into any catastrophes along the way that could not be overcome.”

The Enchanted Laboratory of Nostramos the Magnificent opened on June 22, 1986.

“We delivered the project on budget,” Wade states. “It was a huge success, and all the angst that occurred to get there is forgotten by everybody because the public so embraced the show.”

“We were in the early part of our careers, and this show really hit on all cylinders,” says Ted King. “It was one of our first artistic and critical successes and ran for 15 years.”

“What was important was that audiences loved it,” Gary Goddard explains. “It really played well. I’m most proud of the fact that shows and attractions we created do not talk down to audiences. Most theme park shows have been ‘dumbed down’ because management thinks that theme park audiences cannot follow a real plot, nor do they care about dramatic narrative. But as shows like The Enchanted Lab, Terminator 2/3D, and even The Amazing Adventures of Spider-Man ride have proven: you don’t have to dumb down rides or shows in theme parks. Done well, shows that require audiences to be engaged in the story can work, when they are done with an eye to quality.”

“The Enchanted Laboratory project still to this day ranks as one of my three most favorite projects,” continues George Wade. “It’s very near and dear to my heart. What Landmark’s creative team was able to do was to create a show that had tremendous heart and soul, and the audience became emotionally attached to the young boy Northrup as a character. We created a show that people were emotionally engaged with on a very stringent budget, and it showed that you don’t need a huge budget to produce a project that’s going to be embraced by the general public.”

“It was a great working relationship with everyone at Landmark,” Joe Peczi says, “as well as all of the vendors involved in creating the animatronic figures, illusions, scenic execution, lighting, music, and effects. This show will always hold a very special place in my heart as one of the best productions with which I was involved in 31 years with Busch Entertainment Corporation.”

Along with the opening of the attraction, an accompanying retail shop – Wizard Works – opened approximately in the middle of the Hastings area.

Once launched, director Rich Hoag was never officially brought back in to “tune up” the current cast of Northrups. “I happened to be there for another project, poked my head in, and introduced myself to the new Northrups” Rich recalls. “Attractions of this nature, with so many effects involved, are likely to have technical issues over time, but there were very few. The fact that the show ran for fifteen seasons is a tribute to the creative ability and technical know how of those involved.”

Although the human actors didn’t get any tune-ups for the original creative team, their animatronic counterparts did. “About 11 months after the project opened,” George Wade recalls “we put a team together—one person from the special effects side, one from animation side, one person from the set standpoint, and some of our core people—and we performed a complete warranty check on the show. The people at Busch could not believe that Landmark would do that, and we said ‘Look, we stand behind our work, and we want this show to continue delivering a quality experience to your guests. A month from now, it’s going to be out of warranty, so we wanted to come in and do a checkup on it and just make sure that you’re in good hands.’

“Part of that was it’s the ethical thing to do that no one ever does,” Wade continues. “Part of that was we wanted to keep an excellent relationship with Anheuser-Busch, and ensure that the folks at Busch Entertainment would want to do another show with Landmark Entertainment.”

Over the years, subsequent Northrups were trained by Busch Entertainment staff, and the Northrups that came before them. “The training process involved being sent the script and CD,” recalls David John Madore, who played Northrup in the summer of 1998. “When we arrived at the park, after orientation and all that, we were taken into the lab and shown around how all the tech worked and all, and how not to break things.”

“With most theme park live shows, you have a cast of maybe eight people, and that show can only run four times a day because the cast can only do so many shows,” project manager George Wade explains. “With The Enchanted Laboratory, they had multiple Northrups in a given day, so they would trade off doing the show. Each would do, say, one show per hour over an eight hour shift with time for a lunch break in there. So Busch Entertainment found the show to be a beloved guest experience, with low operating costs.”

“I believe one performer would do two shows in the morning,” remembers David John Madore, “before the other actor would show up to do the third show, and start the switch-off. Then a third would relieve the first, and he would have to do the last two shows of the day.”

Early in the process, several handheld magic tricks were taught to the actors. “One was the colored cloths, and another was the collapsing magic wand,” Madore continues. “They also tried to teach us a rope trick to do during the pre-show,” but this magical feat was optional, so not all Northrups performed it.

“Then we watched one of the trainers go through the track for us, talking through the lines, while we read the script, taking notes,” Madore remembers. “After that, it was trial by fire! We went through the show, each of us watching the others make utter fools of ourselves, or not, and then they gave us corrections and suggestions for the next run. There was also expert dialect coaching by Emile Trimble (then head of casting at Busch Entertainment), as we had to do a British accent. Some of us got it a lot better than others, and a few abandoned it altogether, it seems.”

Tony Pinizzotto began his Busch Gardens career as an actor playing Northrup, and later became a stage manager, directing new Northrups as well as strolling performers. In his first year as a Northrup, Tony recalls “Steven [Woolworth] and I rotated in the spring and two days of the week the lab would have six shows (so we could each get a day off). All the other days there would be 12 shows (six in the day and six at night). There were shows back-to-back-to back almost every half hour, with the exception of twice a day where there would be 45 minutes between a few shows.”

During the peak season of summer, as many as five actors would play Northrup, each performing six shows per day, for a maximum of 30 performances on weekends.

“Meal breaks involved getting to go anywhere in the park, to eat,” Madore continues. “Backstage had special employee counters for each restaurant, so we wouldn’t have to mingle with the guests too much, though it was a treat to run to France and get a strawberry sundae on really hot days.”

“I think Busch’s expected lifespan for the show was somewhere in the five year range?” Wade says. “So it is amazing that the show got the life that it did. It was just the stars aligning in a way that rarely ever happens in entertainment. Again, there were so many people that contributed, but the fact of the matter is that it was a set of rare and unique circumstances for it to get a fifteen year lifespan.”

The ran virtually unchanged until 1989, when Emile Trimble, then Busch Gardens’ Director of Entertainment, decided to make some adjustments.

“She was given the power to alter the script,” explains Steven Woolworth, “and she did so extensively by cutting out any and all anachronistic jokes.” Steven was hired in 1989, and was among the first Northrups trained on Laboratory 2.0. “I had never seen the show before so I had no idea we were performing a ‘new’ version. We learned so after we started to performing and park vets were checking out the show and saying things like, ‘What happened?! The show used to be funny!’ Emile really went to war with her bosses over the changes and finally had to put some of the jokes back in.”

“Some say she took a lot of the ‘jokes’ out of it,” explains Tony Pinizzotto, who also joined the show in 1989, “but I know she was trying to make the show more all-around family friendly. We still worked a few jokes back in as the summer went along.”

“Even stranger is that [Emile] also restaged a lot of the show,” Woolworth continues. “She couldn’t mess with the illusions which dictated our placement on stage but everything else was fair game. It was all well and good except for the fact that the lighting plot was never reprogrammed after the restaging. This led to us boys delivering a lot of dialogue in the dark while spotlights and specials were lighting other parts of the stage reflecting the original staging.”

It’s unclear whether the script and staging changes ever fully reverted back to their original form.

Laboratory closed on August 18, 2000. In the fall and winter months that followed, Hastings was reimagined as Killarney, Ireland, and with the new area came a new show. Secrets of Castle O’Sullivan was designed by many of the same artists as its predecessor, and ran from the 2001 through 2008 park seasons.

After Castle closed, the audience seating was reconfigured to include partitions at each seating level. Benches were taken out, replaced with tables and chairs for a dinner theater layout. With a few modifications, the Castle set was used from 2009 through 2015 for a Dine with Elmo and Friends breakfast and lunch show. “A Frugal Chick” reviewed the dining experience in June of 2014; click here to see photos of the converted stage and seating.

As of 2019, the theater is only open for special Halloween and Christmas events, such as Santa’s Fireside Feast, when Christmas trees occupy the spots formerly held by Rimshot, the suit of armor, and the flying pillow.

Catapult scrambler ride, 1976 (Courtesy of Gary Terrell)

The Hamlet of Hastings, 1975. The castellated building at the bottom housed The Catapult (Photo by Buddy Norris / Daily Press)

Hamlet of Hastings, Laboratory at right, June 1990 (Courtesy of Gary Terrell)

Watercolor concept rendering by Joe Peczi, 1985

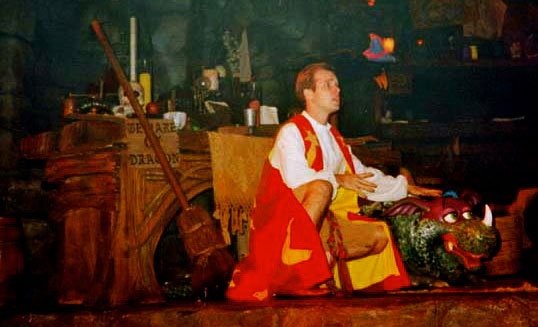

Northrup comforts Talon (Dan Walsh as Northrup – Photo courtesy of CastleOSullivan / Tyler Whitby)

Show model (Photo courtesy of Terri Cardinali)

Animatronic wall gargoyle (Repurposed later as Howl-O-Scream set dressing – Photo by Chuck Campbell, 2014)