Thanks for Joining us!

Here’s your Kings Island map file and preview chapter. Bookmark this page or print for later, then browse the site for other good stuff.

Kings Island 1972 souvenir map (300dpi, 28x25, 28M, click to be directed to the full-size file)

Davy Crockett tangles with…Yogi Bear?

Surveying the muddy waters that had just submerged the park, again, Gary Wachs knew something had to give. It wasn’t just the recurring floods, an inescapable penalty from building right up against the mighty Ohio River. The old, wonderful park was landlocked with nowhere to grow. And grow it had since its humble start in 1870 as a picnic retreat in an apple grove. Coney Island thrived as one of the most enduring and popular amusement parks in the country.

Perhaps more than a little of this can be attributed to its borrowed name, though of no relation to its more famous namesake. Not long after becoming a popular local amusement area, Coney, or rather Parker’s Grove at the time, attracted the attention of a couple riverboat captains who, in a unique twist to the trolley park trend of the day, operated riverboats along the Ohio to bring folks to the grounds. The new park was now called Ohio Grove, the Coney Island of the West. Over the years and decades new amusements and entertainment would be added, including its first coasters in the early 1900s. 1913 saw the first of several floods that would, ironically, serve to propel the park forward through the necessity of rebuilding newer and better. Transfer of ownership from time to time also brought renewed investment, and the crowds swelled from the nearby regions.

Unlike so many similar parks around the country that struggled, fizzled, and flamed out through the ups and downs of changing economic and social conditions, Coney stood its ground, maintaining beautiful facilities, quality attractions, and a reputation that brought no less a figure than Walt Disney out to see for himself as part of his early park research. It was a booming place in the 50s and 60s. And then came the 1964 flood, 14 feet high and covering most everything except the rooftops and spectacular hills of the Shooting Star and Wildcat coasters. As Gary grabbed a broom and shoved mud off the walkways, his mind raced in all directions. What to do? The park has survived this before; we can rebuild. But we’re out of room; nowhere to grow. Can’t accommodate bigger crowds. He also realized the park business was at the cusp of a major shakeup with the success of Disneyland and Six Flags Over Texas, representing a new concept of the regional theme park. That’s the direction they needed to go in order to survive, and they couldn’t do it here at Coney. And then the unthinkable solution—move the park. How on earth do you move an amusement park? He wasn’t sure yet, but the more he thought about it the more convinced he became.

That was the easy part. Gary was but a 28-yr old assistant manager, the president’s kid who was helping run the company. So when he laid the idea out on the table, dad didn’t take too warmly to it. Ralph had been there a long time and, understandably, none of the elder management team could fathom such a drastic change at a time when attendance was at an all time high. The park was performing as good as ever. Most companies look to a different direction when they’re in trouble, not at the peak of their game. Young Gary kept at it, never wavering, but needing a break to help make his point.

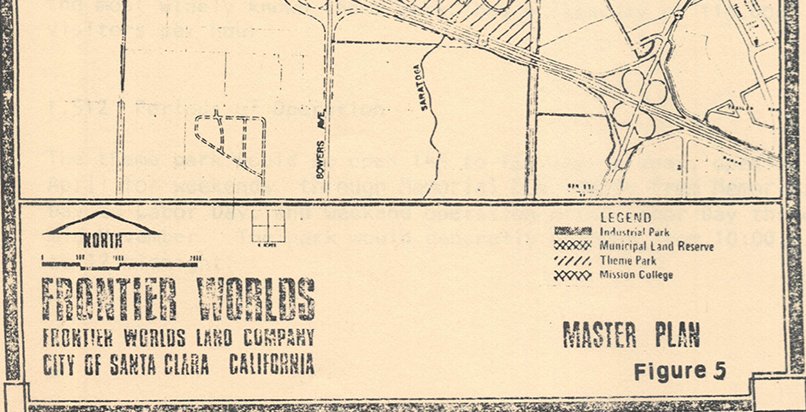

He got it in 1968 when Fess Parker, known to all as Davy Crockett, announced Frontier World. The regional theme park would be built in Boone County, Kentucky, practically next door to Cincinnati. With a single headline, Coney’s team realized Gary had been right and that such a project would most likely wreak havoc on their park. He was given the green light to investigate options, particularly finding a partner with a much larger checkbook to help finance such a major initiative.

The white knight turned out to be Taft Broadcasting, owner of the Hanna-Barbera cartoon franchise and who was looking for new opportunities to monetize the brand. Taft’s interest in the project got a major boost after a long lunch consultation with Roy Disney, who ironically pointed out that it was Ed Schott, then-owner of Coney in 1953, who enthusiastically encouraged Walt to pursue his own park. The final doubter was converted after showing the skyrocketing stock value of the company who had just bought the first two Six Flags parks from Great Southwest. Coney was purchased for $6.5 million. 1600 acres was then acquired northeast of Cincinnati and a deal struck to build a $30 million theme park along with a motel and golf course. But the first order of business was to shut down Parker; Taft was powerful in that area and the financing well suddenly ran dry for Frontier World. Funny how things go in the world of business. With no options left, Davy Crockett laid down his musket and traveled west to try again in California.

* * *

Construction on the as-yet-unnamed park began in 1970. Bucking an industry trend, the decision was made to keep all design work in-house; Duell & Associates would have no part of this new endeavor. A notable exception, however, was the hiring of Bruce Bushman. A former studio artist-turned-art director for Disneyland, Bushman had overseen Fantasyland, designing the fanciful Casey Jr. Circus Train with its whimsical ticket booth and the ride vehicles for Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride, among others. He would be responsible for giving International Street its majestic, yet intimate look and feel, unfortunately passing away just before the park opened in 1972.

While all of this was getting underway, Coney Island was gearing up for its final season with a new Galaxy roller coaster and lots of marketing. Taft had quietly left the impression early on that Coney would continue operations, presumably to deflect any backlash towards the new project. Investment in the old property had continued with an Arrow flume ride in 1969 and a Hanna Barbera show theater the following year. For the 1971 season, however, promotional materials talked up the new park in an effort to persuade folks that, yes, things were going to be even better at the new place. Coney’s final days were spectacular, with 2.75 million guests pouring through the turnstiles to say goodbye. Surely everyone in management was holding their breath, wondering and hoping they had made the right decision. What if people didn’t take to the new park? Look how unbelievable this year has been—are we nuts? They would find out in short order.

Meantime, over at the project site things were kicking into high gear. Wachs and his new team explored the nooks and crannies of their acreage, considering what to build and where to build it. Toward the back of the site was a wooded area and ravine—perfect for a train trestle and surrounded by what would become Rivertown. The remaining lands would be arranged in a hub-and-spoke configuration radiating outward from International Street and the Eiffel Tower: Oktoberfest, Happy Land of Hanna-Barbera, and of course, Coney Island. The Eiffel Tower, a $1.2 million grand 1/3 scale replica of the original, would be the icon of the park. Interestingly, the tower had been contracted earlier for installation at Coney. Once the decision was made to move, it was put on hold with Intamin, a major ride manufacturer in Switzerland. Several attractions from Coney would actually be transferred once that park closed at the end of the 1971 season.

With ample acreage the designers had room to play, and for a group who for the most part had little experience designing theme parks the result was quite successful. Gary had spent a great deal of time visiting parks in the United States and Europe and had a pretty good idea of what he wanted to do. Even so, it would take over 150 tries to figure out the park’s eventual layout. Taft stayed out of the way and let him figure it out. By now they had a name—Kings Island, a combination of Kings Mills (the previous property owners were the Kings; the adjacent town was Kings Mills) and Coney Island from, of course, its predecessor. An August 1970 naming contest had brought in over 15,000 entries with local resident Rebecca Richards coming out on top, winning a week-long trip for four to Hollywood.

* * *

The front ticketing and guest services building effectively concealed what was in store for park guests. This was deliberate, the designers understanding that the cinematic reveal as guests walked through and saw the Eiffel Tower and majestic Royal Fountain was a powerful, dramatic transformation. International Street was inspired from European parks and the recent New York World’s Fair, with carefully manicured green spaces, fountains, flags, and colorful architecture. It also, along with much of the park, pays tribute to the various immigrant communities settled in that area long before. It’s a beautiful promenade with various shops and restaurants along each side all set to European themes, organized in “city blocks” according to country: Auld Suisse Haus, Geselleschaft Deutschland, Fiera Italiana, La Tienda Espana, and Bazaar Francaise. Grab lunch at Kahn’s Sausage Haus or Munchen Cafe, let your kids pick out a stuffed animal at Spielwaren, don a shirt from Hute-Hemden, buy a bracelet at Bijouterie, watch a glass blower at Cristaleria, and don’t forget your candles, available at Kerzen. Small details make a difference; the cobblestone pathways lining International Street were from Colerain Avenue in Cincinnati. The animal themed countertop of the Italian ice cream shop was hand-made tile, and a pair of original chandeliers from Cincinnati’s 1878 Music Hall hung high in the Swiss chalet.

And there was more, but branching off to the right of the Tower was the Happy Land of Hanna-Barbera—the main reason Taft got into this business in the first place. This was no mere kiddie land; it featured significant attractions such as the Scooby Doo wooden coaster, Marathon Turnpike car ride, Gulliver’s Rub-A-Dub water raft ride, and, most interesting of all, the Enchanted Voyage. This $2 million boat dark ride was housed in a large show building designed to look like you’re floating straight into a television set. The Arrow-designed flume system had a unique turntable load/unload platform outside of the main building. The show itself consisted of six scenes all filled with Hanna-Barbera characters, animatronics—all 100 of them, and elaborate music that was scored in Hollywood and reproduced in surround sound.

The Sky Ride Station offered a cross-park hop over to Oktoberfest, passing directly in front of the Eiffel Tower. Unlike a pure hub-and-spoke layout, pathways connect each of the two lands on either side of the tower without having to return to the hub. Rivertown is next, paying homage to Ohio’s rich history of river life and related trades. The Arrow flume from Coney was relocated here as Kings Mill and the Kings Island & Miami Valley Railroad offered a steam-powered excursion off into the woods. The two narrow-gauge locomotives, modeled after the Civil War General, departed Losantiville depot, the original name for Cincinnati, and set off for staged train robberies and live-action fights between frontiersmen and Native Americans. Rustic, frontier architecture and water features set the scene in this area. Kings Island would not have a Jungle Cruise look-a-like, but here in Rivertown there were two canoe attractions, Shawnee Landing and Kenton’s Cove, the latter of which would last only the first season before being replaced with an Arrow hydroflume. Great Rivers Outfitters, Columbia Palace Dining Hall, and a General Store provided places to browse, eat, and shop before heading toward the back of the Eiffel Tower. Here was another car ride, actually two of them intertwined—Les Taxis and Ohio Overland Auto Livery. One load station faced Rivertown, the other opposite toward Coney Island.

Coney Island. Of course there’d be an area dedicated to remembering where it all came from. The midway, pretty much like it was at the old park, was lined with green planters and gingko trees shaped kind of like corn dogs or something (actually the same trees transplanted from old Coney). Whereas Disney and Six Flags had deliberately avoided any resemblance to the amusement parks of yesteryear, Kings Island would pay tribute. And why not? Coney was nowhere near the typical, disreputable, carny sort of place and held fond memories for the locals. Games and amusements lined either side, including a few classic flat rides brought over from the other park, but the big attraction is what commanded attention running the length of the midway and beyond. Racer was a magnificent dual-track wooden coaster built by famed coaster designer John Allen. Pursuaded to postpone his long-deserved retirement, the task was to bring the spirit of Coney’s Shooting Star while taking it to a new level. It spawned two similar rides at Kings Dominion and Carowinds and helped launch a renewed era of wooden coasters, something that had nearly died away completely before Gary came a-calling.

The final themed area of the park, Oktoberfest, was the smallest with a few rides and bier garten surrounding a small lake. There was a drunken barrels flat ride, found in most parks of the time, and a Galaxy coaster, Bavarian Beetle, also relocated from Coney. The oh so very German-named Sky Ride Station connected with Hanna-Barbera Land. The Der Alte Deutsche Bier Garten was (and still is) an expansive, well-themed structure situated on the lake with scenic outdoor seating.

Just off the hub toward Rivertown was the obligatory dolphin show, and connected directly to the Eiffel Tower was the Carousel and a rather strange, bright red inflatable structure that was used for shows. The rather pretentiously named Kings Island Theater didn’t last too long, giving in to heavy snows after a few years. Cheap to build at the time, it got the job done, but certainly the park’s aesthetic value rose a few ticks after its demise. Most of the park’s entertainment was not housed in show buildings, however, but situated outside all around the park. The individual hired to run the shows department, Jack Rouse, would go on to establish JRA, one of the most successful themed design companies in the world.

In addition to the park, the designers borrowed the concept of a resort destination that other parks had incorporated. The alpine village-themed Kings Island Inn, Kings Island Campground, and even the Jack Nicklaus Golden Bear Golf Courses completed the package, particularly important for an area that had very little development at the time. There was simply nothing there, but of course that was about to change.

It may not have had the Duell touch, but it was a beautiful park and an immediate success for its owners. Somehow management had come up with a first season attendance prediction of two million, a staggering number at the time that no other park outside Disney had approached. By the last operating day of 1972, attendance had clocked in at two million twelve thousand.

* * *

Taft Broadcasting lost no time looking to expand their new venture. Even before Kings Island opened as an unqualified success, the company sought locations to build more parks, first settling on 1300 acres of land just north of Richmond, VA, alongside Interstate 95. Land was cheap at the time, the climate was right, it was close to major population centers, and the Interstate provided easy access. $60 million was allocated for construction, the largest spent on any park outside of Walt Disney World which had opened just a couple years earlier. Dennis Speigel, all of 29 at the time and working under Gary at Kings Island, was sent east to oversee construction and manage the park once it opened.

The public announcement in 1973 included an artistic “map” of the property. The “Kings Dominion 800-acre development plan” shows Lion Country Safari, the theme park, golf course, “motor inn”, camping, and future expansion plots. Taft had worked with Jack Nicklaus on Kings Island’s golf course, and they were entering into an agreement with Lion Country Safari, Inc. to open a drive-through safari at the Ohio park. Lion Country already operated locations in Florida and California; the Virginia safari would open in 1974, one year before completion of the park.

Lion Country was initially a drive-through experience with guests cruising through the animal preserves in their personal cars. This was a mixed bag, with lions, elephants, and other rather aggressive creatures chewing, ripping, and clawing everything. After constantly shelling out to buy new tires, fenders, and paint, the park finally installed a monorail that snaked around the compound in air conditioned comfort.

Meantime, an experienced team exported from Kings Island was frenetically working to get the park open. Hundreds of daily decisions had to be made in a project of such a scale as this, usually on-the-spot with little time to think about any long-term consequences. Lucky for them there were few major hurdles along the way; no opposition from the locals, no environmental snags, no financing drama. The company had already done this before, and that invaluable experience provided a roadmap throughout the process. Rising inflation in the 1970s didn’t help, however, dramatically increasing construction costs and threatening to blow the budget. Half of International Street, the promenade that ran along the central fountains from the front gate, cost twice as much to build as the other half. In spite of all this the park opened on time and under budget. The folks from Kings Island were fairly young, ambitious, and ready to tackle anything. Sometimes it pays to be just a bit unaware of the enormity of the task.

May 3, 1975—opening day. By 6am the lines were out into the parking lot, with traffic ultimately backing up for miles on the Interstate and local roads in every direction. The park gates were opened early…and by 9am closed again after tens of thousands of people rushed in. Thousands more were turned away that day. The following week the park placed ads in the local papers apologizing for the madness and reassuring guests that they were working hard to keep it from happening again. Changes included limiting the number of visitors in the park each day and encouraging people to come during the week “when you’ll have the park more to yourself”. In fact, the state had to pitch in with Taft to improve the I-95 interchange in order to prevent cars from backing up on the highway. The team had successfully established the message and brand of Kings Dominion in an area of the country that was as yet unfamiliar with the concept of a theme park. Busch Gardens would open one week later just down the road near Williamsburg, but for the moment KD was the new thing in town. Projected attendance for the season was 1.85 million, and they were well on their way.

* * *

The park’s name is a mash-up from Kings Island and Old Dominion, Virginia’s nickname. Perhaps reusing Kings Island to maintain a consistent brand would have been logical, but it really didn’t seem to matter once the park was open. From a thematic perspective it actually makes better sense to localize it for the area, and this probably made for a much better choice in the long run.

Borrowing heavily from its older sibling, the park’s design is pretty much the same, greatly streamlining the design and planning process. Other than the Safari, there would be one less land; all but one of these would be themed the same as at Kings Island, the exception being to convert KI’s Rivertown to Old Virginia. In both cases this was a nod to local history.

The entryway opened onto International Street and the central fountains, just like in Ohio. The Eiffel Tower again serves as the central icon at the end of the Street, branching off into the various lands. The architecture and layout of International Street was somewhat different, however, but still retained the international flavor. You could pick up a plush at Toys Internationale, find fudge at Coffelt’s Swiss Treats, score a sandwich at the Sunbeam Alpine Deli, and on the way out sit down for an evening meal at the Casa Del Sol Restaurant after getting those last minute souvenirs from the Italian Emporium and La Piñata Gifts. At both parks, International Street was a beautiful center of activity with sculpted landscaping, dancing fountains, and the inspiring Tower rising above it all.

In the upper-right quadrant was Old Virginia, heavily wooded and themed to represent simpler times. After crossing over a mountain stream, to the right was the Shenandoah Lumber Company, an Arrow-built flume ride scenically nestled in the trees. To the left, the Blue Ridge Tollway auto ride wound its way around the countryside. Take in a show at the Mason-Dixon Music Hall, then all-aboard the Old Dominion Line steam railroad for a mile long journey deep into the woods through Moonshine Valley and Harmony Junction. Ida Lou, who's back from the city after failing to find her a man, has her sights set on the train's conductor. If he doesn't do her right, Pa's awaitin’ at the end of the line with his shotgun.

Soon's the train stops, scoot off the platform and turn right out of the station, heading over toward Lake Charles and the imposing, intimidating racing coaster Rebel Yell. This younger brother to Kings Island’s Racer is similar, but with the turnarounds pushed together in order to accommodate the Safari. For the first season, this area was named Coney Island and laid out very similarly to Kings Island with its midway flavor and gingko trees (it became Candy Apple Grove the following year due to negative connotations with the original New York Coney, the locals not having any connection with the more wholesome Cincinnati Coney). Grab a candy apple after riding the Galaxy coaster and take in the Wachs Bros. Mecham & Runyan Circus, situated on a spit of land jutting into the lake.

At the far end of Coney Island lay the Happy Land of Hanna-Barbera, dominated by the Scooby Doo roller coaster and Whacky Wheels turnpike. If the kids will sit still long enough, they have a choice of either the Flintstone Follies or Scooby’s Magical Mansion magic show. Journey into Yogi’s Cave and explore the famous bear’s colorful, animated world, carefully crafted at a cost of $1 million. Inside you’ll ooh and ahh at the “precious gems” of “Rooby Falls” and listen as “The Genuine Rock Bandorgan” echoes among the intricate concrete rockwork. Then grab the handrail as you try walking through the ranger’s cabin, tilted at 18 degrees with water flowing uphill. Now say goodbye to Yogi and head back, either following the pathway to the right which takes you back to the Eiffel Tower or jumping on the Sky Ride, offering an aerial hop back over Coney Island to land in front of the Rebel Yell.

The Safari tour served as the park’s fifth land. The “motor inn” was added later in the front section of the parking lot, but no Jack Nicklaus golf course. Strangely, to this day there’s not much development around the park other than a few small hotels, a Burger King, and the old truck stop that was there long before Taft showed up. Nevertheless, Kings Dominion was wildly successful and has remained steady over the decades in spite of various changes in ownership.

* * *

The third park in Taft’s strategic plan took awhile to get going. By this time Taft had partnered with Family Leisure Centers (Kroger) and was looking north for this one, in 1973 acquiring land in the region of Toronto, Canada, specifically the village of Maple (in the town of Vaughan). But the idea of an amusement park—and especially an American-based one—didn’t sit too well with the locals. In a scenario that would become all too common for park planners over the decades, it was going to take serious politicking and education to convince them it might actually be good for them. Locals banded together as SAVE (Sensible Approach to Vaughan’s Environment) while regional cultural centers such as the Royal Ontario Museum worried about competition. “For God’s sake, Disneyland isn’t the real world. We don’t need a place like this. We have everything we need in Metro Toronto…It’s an abomination and I don’t want my children exposed to more of this kind of hucksterism,” said an enraged Margaret Britnell, mayor of King Township.

Taft realized none of these people had any idea what such a park would be like—there was nothing else in Canada for comparison. So they hosted a tour of Kings Island for the folks to get hands-on with what they had to offer. Reaction was somewhat mixed, but overall the group came away with a new perspective. The mayor of Vaughan was an enthusiastic supporter. “That was a great public relations thing for them to do.” “All this anti-American feeling is baloney. Building this park is no different than watching American television.”

Opposition to the idea, however, was just cranking into high gear. Toronto city councillor John Sewell insisted “we should do everything possible to discourage this proposal.” Other local officials chimed in, and SAVE kept up the pressure. By 1978, however, enough of these individuals had a change of heart, and in March the Ontario Municipal Board issued a 32-page report approving the project, including a key stipulation that the park emphasize Canadian culture in the design. Not all came away happy. Local councillor James Cameron rued to The Star “You could say Yogi Bear won and Maple lost”. “Resignation has been the real response of the people,” SAVE told the Star in 1980. “It means we’ll be living between two dumps.” Dumps? Oh yes. The park…and the Keele Valley Landfill.

Ground was finally broken for Canada’s Wonderland in 1979, with the park opening two years later. True to Taft’s expectations, the park was a hit, with first year attendance nearly breaking 2.2 million. It has since gone on to shine as one of the most attended regional parks in North America with nearly 3.8 million guests in 2018.

* * *

To their credit, Taft initially set out to design a park that was identifiably Canadian, rather than merely copying from the other two blueprints. The overall layout and entry concept remained, including International Street, the central fountains, and the park’s towering icon at the far end. But in this case it wasn’t a tower—Wonder Mountain with its majestic, cascading waterfall signified Canada’s beautiful, rustic landscape and provided not only a visual centerpiece for the park, but also a vantage point for viewing the surrounding area. Wonder Mountain Pathway wound up and around the mountain toward the peak, which did nothing for preserving forced perspective of height, but provided lots of Kodak camera moments. International Street resembled the ones at Kings Island and Kings Dominion in its colorful, international architectural style. Interestingly, instead of indicating specific shop and food locations, the first-year park map simply labels the Alpine Building, Scandinavian Building, Mediterranean Building, and Latin Building.

Off to the right through a well-themed portal lay the land of Medieval Faire, where everything is spelled accordingly: Dragon Fyre, French Fryes and Shrymps, and Yee Ribb Pytt give you the idea. An impressive castle facade led into the Canterbury Theatre, while the Sea Septre sailing vessel dominated the small lake as part of the pirate stunt show. Moving to the upper-right quadrant of the park we of course find the Happy Land of Hanna-Barbera, complete with an Arrow auto ride, carousel, dolphin show, and Yogi’s Cave. With Canada’s Wonderland opening later than the earlier regionals, roller coaster technology had developed and therefore the park featured several coasters, including the family-friendly Ghoster Coaster, complete with a wonderfully detailed station building and graveyard.

Returning back behind Wonder Mountain finds us in the lower-left quadrant where everything reflects the Grande World Exposition of 1890. Rides, food, and shops were styled and named in international flavor, such as Ginza Gardens, Moroccan Bazaar, Swing of Siam, and Persia (yes, just “Persia”). Now, sitting on the upper-left edge of this land was the Mighty Canadian Minebuster roller coaster. If you happened to notice, we skipped an entire quadrant on our journey around the park, seeing only three lands spread around International Street and the mountain. Remember that caveat for approval from the town? The bit about emphasizing Canadian culture? Well, it didn’t happen. As construction developed and budgets were updated, it became clear something had to go—Canadian Frontier…or the Happy Land of Hanna-Barbera. You can guess which way it went. “You could pick this thing up, lock stock and barrel, and move it to Pretoria and call it South Africa’s Wonderland. There is nothing Canadian about it at all.” The Minebuster was about all there was for thirty-eight years before the park finally added a small section shoehorned between the mountain and the water park.

* * *

And there was yet a fourth park in Taft’s plans, this time in the land down under. Australia’s Wonderland opened in 1985 as a joint venture and, while sharing similar concepts from the Canada park, was nowhere near the scale of its sister. Missing was International Street and a park icon dominating the skyline. Guests entered the turnstiles, looked up the path, and saw Bounty’s Revenge, a standard swinging pirate ship flat ride. It consisted of three lands, Happy Land of Hanna-Barbera, Medieval Faire, and Gold Rush, with many borrowed attraction concepts from the other Taft parks.

Unlike its siblings that continued to expand and survive to this day, Australia’s Wonderland went through ownership changes that eventually led to its demise in 2004. Then-owners Sunbury Group blamed the economy, 911 terrorist attacks, the Asian bird flu, and pretty much everything except their own doing. In a pattern that’s all-too-familiar to park enthusiasts, the site has been converted into an industrial park. But scattered around the periphery are the rotting remains, still haunting the grounds to ever remind us of what we once had.

* * *

Did we say Taft had four parks? Not so fast—there was a fifth property, this one in the works while they were building Kings Dominion and negotiating a (failed) merger with Cedar Point. 800 acres had been optioned at the intersection of Route 47 and the Northwest Tollway, near the town of Huntley in Kane County, just outside Chicago. Kings World was announced in 1973 while Marriott’s Great America was getting into gear; both companies recognized significant opportunity in a virtually untapped market. Taft’s proposal called for a Kings Island-type park, a 200-room hotel, golf course, campgrounds, trails, and exposition halls. As part of the company’s site studies, a height test was run to determine visibility of the iconic 450-ft tall Eiffel Tower (it would have been seen from four or five miles away). A 12-ft high earthen berm was planned for the two sides of the park facing Route 47 and the Tollway to contain noise and eliminate visual intrusion. Retention ponds would hold run-off from rains, and water studies determined no negative affects on the area supply. Taft even planned to build their own sewage treatment facility and pay for improvements to the highway intersection leading to the park.

No matter, the plan immediately ran into all sorts of local opposition. In spite of the promise for jobs and positive economic impact on the region, many could only envision the traffic, congestion, noise, skyrocketing land values (and the associated property tax increases) and whatever else came to mind. A local group even banded together as the Rutland Environmental Protection Association and filed a complaint with the Illinois Pollution Control Board against Family Leisure Centers (Taft). Their beef? That the park would deplete and pollute the ground water supply. To be fair, both sides have legitimate issues. Building a major entertainment facility brings with it a slew of good and bad stuff. Did Chicago lose out by sending Yogi back to Cincinnati? No telling, but this scenario would be played out more than once as we shall see.

* * *

Gary Wachs could never have dreamed of the far-reaching legacy he’d leave. After all, he was just trying to plot a survival strategy for old Coney. But three out of four parks born from his crazy idea have thrived, survived a few ownership changes along the way, and thrilled millions of guests over nearly half a century.