The MArriott Parks

-

History of the parks

-

The 3rd park, Pt 1

-

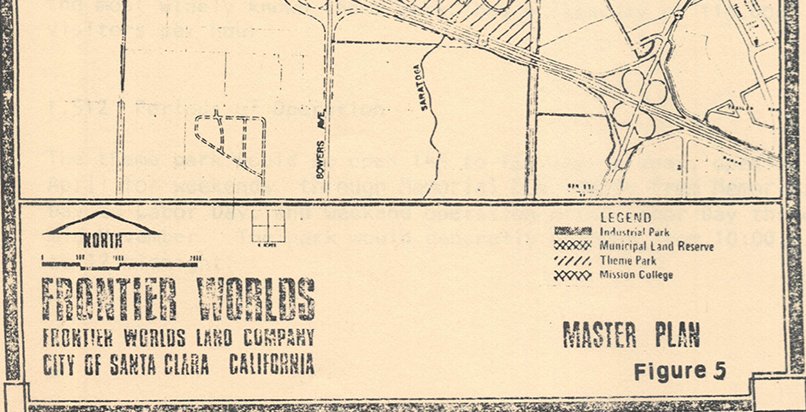

The 3rd park, Pt 2

-

The 3rd park, Pt 3

-

The 3rd park, Pt 4

-

The 3rd park, Pt 5